by Courtney Baxter, Program and Communications Specialist

“Why is stormwater runoff a problem?”

That is the first line from “Solving Stormwater”, a film produced by The Nature Conservancy, and a question asked by Mark Grey, a local business and property owner in the Fremont neighborhood of Seattle and founder of the non-profit Clean Lake Union.

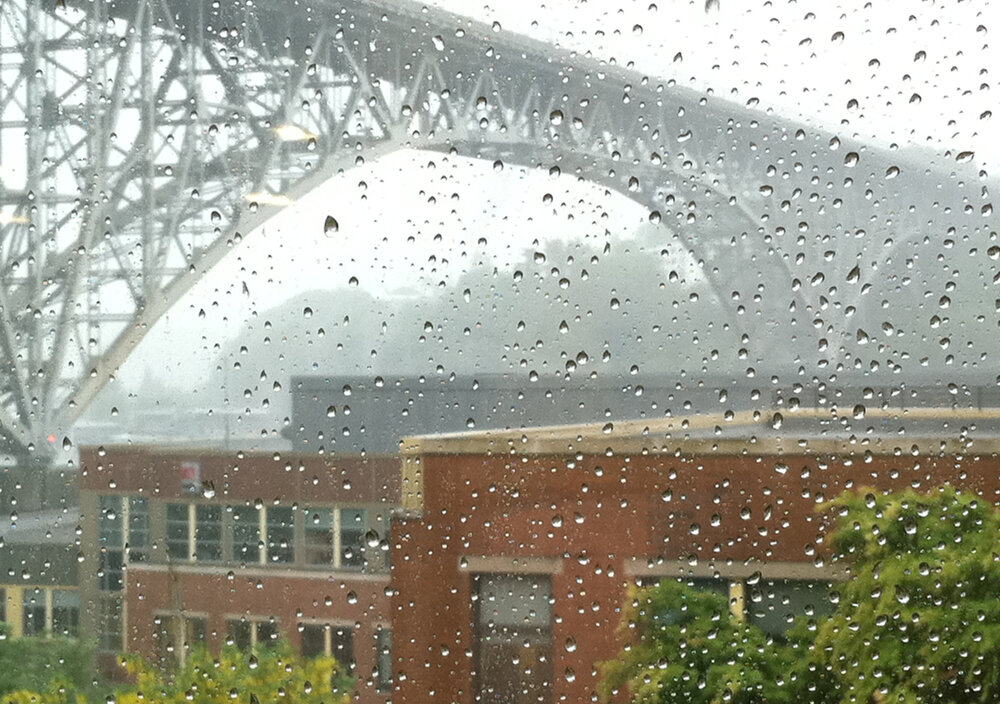

Photo by Heather Van Steenburgh

As a developer of property under the Aurora Bridge, Grey was very aware of the massive amounts of polluted water coming off the bridge when it rained. He could see it pouring down the sides and coming out of the downspouts and going directly into the Ship Canal below. He knew raingardens could clean and filter that water and wondered if he could incorporate rain gardens into his new building’s landscaping design to help? He and his development company, Stephen Grey and Associates, decided to construct a rain garden to catch and clean this water before it headed out to the canal, but it turned out to be a bigger lift than they thought. He needed help.

Photo by Courtney Baxter/TNC

He connected with Ellen Southard, with Salmon Safe, who then connected him to The Nature Conservancy. Together, these three organizations plus a multitude of partners were able to leverage their own individual skills to put a plan in place. Salmon Safe managed the project on the ground while TNC lobbied for public funding to complement the private contributions from Grey’s company and Clean Lake Union, and navigated relationships with various governmental agencies.

The contractor for the Aurora Bridge Bioswale was Turner Construction, which provided a substantial amount of pro-bono services to bring the project to fruition. They had a long history working with Southard and Salmon-Safe since 2008 as the first contractor to pilot the Salmon-Safe Contractor Standards. This meant a commitment to zero sediment runoff during the construction. Despite its proximity to the ship canal, a project of this scale does not trigger a construction stormwater permit, but Turner committed to the beyond code Salmon-Safe guidelines to ensure the site development was safe for water quality and salmon habitat. (To learn more about these standards visit Salmon-Safe’s website)

Photo by Courtney Baxter/TNC

For such a straightforward project, there were a lot of agencies to work with: the State owns the bridge, the City owns the downspouts, but the State owns the water in the downspouts, until it’s a foot off the ground, then it’s in the City’s regulatory authority. This project was a complex puzzle from the start, and no one knew it. Why did no one know this? Because it was the first of its kind – this was completely new territory.

How do you take public stormwater and treat it on mostly private land, with private dollars, with a private company? That became the new question for this now herculean effort. Hundreds of what-if scenarios could have stopped the team’s forward momentum, but ultimately the status quo of untreated water going into the canal and killing salmon was deemed worse. And thus, an unprecedented private-public partnership was born. The three planned phases of the Aurora Bridge Bioswale Project were completed and a pathway was laid for future projects.

A typical roadside rain garden may treat a few thousand gallons of toxic stormwater a year. With all 3 phases of the Aurora Bridge Bioswale Project complete, the project is treating almost 2 million gallons of stormwater a year. The next project? With the help of Washington State Department of Commerce and legislative champions like Senator Reuven Carlyle, a feasibility study has kicked off for the Interstate 5 Ship Canal Bridge — potentially a 98-million-gallon opportunity.

Photo by Courtney Baxter/TNC

The prospect of scaling and replicating projects like these is not only feasible, it’s necessary. As our population grows throughout the Puget Sound region, we have the opportunity and the responsibility to tackle stormwater issues that threaten our salmon and orca.

“We can’t go back. But we can do what must be done now to go forward.”

No responses yet